Giving software humanity is a strategic advantage. So who will be the “human-first” tech company?

Humans are weird.

We act as individuals but move as groups. We behave irrationally, act rashly, think creatively, and love unconditionally. We’re hard-wired with a bias for narratives and justice. We have the capacity for tremendous empathy but also great evil.

Software is weird.

It does as it’s told, without much backtalk and without care for intent. It has no bias towards understanding emotion, unless it is strictly told how and when to consider it. It can do much we cannot, and yet nothing without us.

Humans and software together are really, really weird.

We act differently, communicate differently, value different things. We really just don’t get along naturally.

Nowhere is this more evident than social apps, software that is explicitly designed to extend our relationships, to give a voice to the unheard, to amplify our feelings and express them more completely or creatively. And yet, many social apps solve for human needs that do not exist. Many times, instead of enhancing our humanity, they eliminate it. Not in a Terminator sense, of course, but by confusing the user or by removing human qualities of empathy and creativity from the interaction.

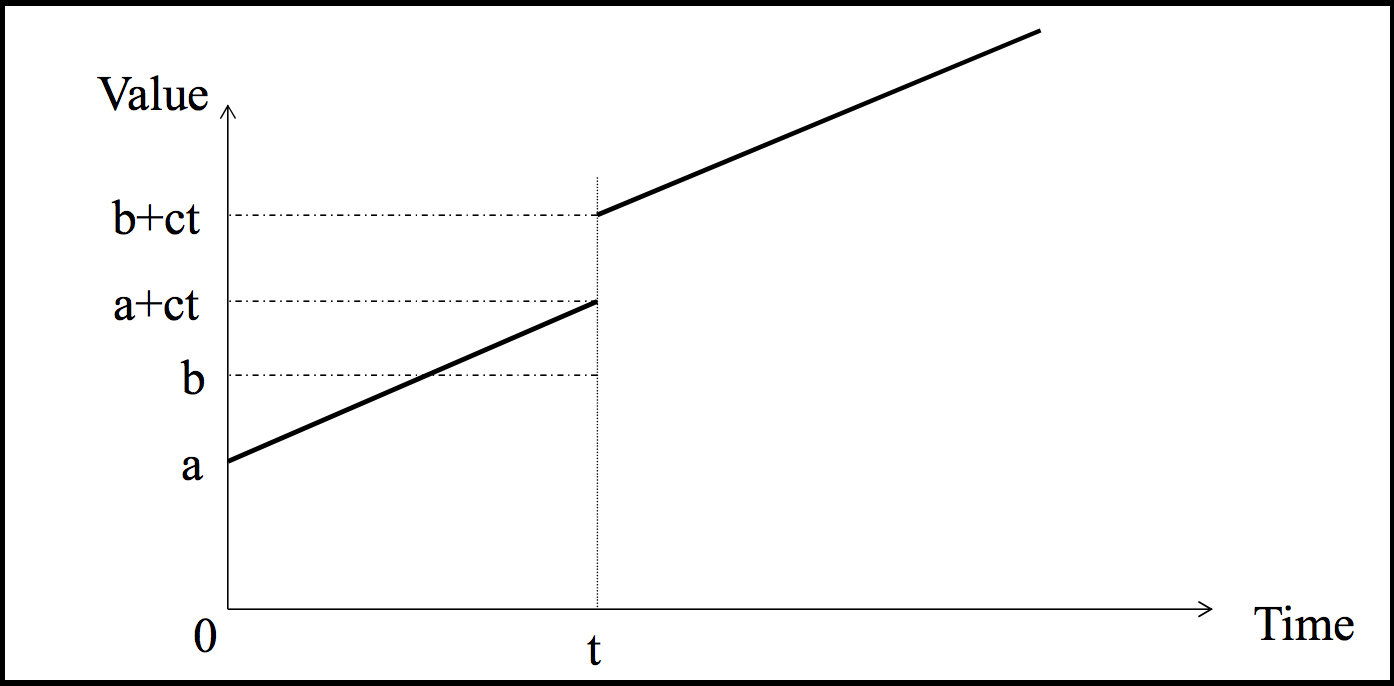

The world of software is changing. The technical hurdle for creating good social products is dropping. Vast networks of scale are no longer a strong barrier to entry for communication products (see: Slack). More than ever, good design is not just about creating the cleanest-looking product — it’s about creating the product that is the most natural to use.

That’s why the best-designed, most human-oriented products now have the potential to win over the current mass-adopted solutions, especially as new platforms emerge and teenagers grow up. I don’t really care which social apps have been successful in the past or how they succeeded. Those first-movers have already moved.

Here’s what I want to know: What product is going to deliberately differentiate on humanity? Who is the “human-first” social network? Who will be the “human-first” tech company?

Endowment: Giving Our Software Humanity

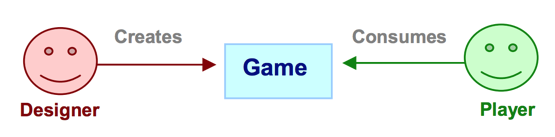

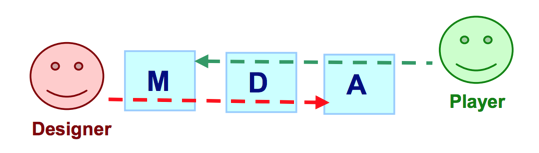

One way we’ve bridged the gap between software and human is by endowing our software with personality. People relate innately to other people, especially if they see themselves reflected. If we sense human character in the software we use, it makes our experiences feel natural and we react positively. At our core, we are social beings.

We’re pretty easy to fool, especially with simple interfaces like text. If you talk with a well-designed chatbot, the experience is often pleasant and effective. Slackbot, Slack’s friendly onboarding bot, is one example of chatbot design done right.

But Slack has also created a vast platform for chat-based applications to thrive, and the response has been inspiring. With the emergence of tools like Botkit, creating powerful interactions no longer requires software designers to have a strong sense of visual design or complex code so much as it requires a deep understanding of human communication and a large dose of empathy for the consumer. Bots don’t have to do and understand everything — they just have to be able to serve one problem or need particularly well. Asking our bots to do too much actually compromises their illusion of humanity as well as their usefulness.

With this emergence of chat platforms and tools to support development, creating powerful experiences, utilities, and businesses is no longer solely the domain of elite technical workers. Anyone with emotional intelligence and an understanding of the humans behind the needs — and particularly how these humans talk about their needs — can build incredible products.

This is what I’m calling “communication-market fit,” not “product-market fit.”

The danger to this is what I’ve written about before: the “uncanny valley” of social communication. If we attempt to create human-like chat experiences with software algorithmically, the software must not try to convince the user that it is human unless it can mimic human interaction perfectly.Surprise: nothing can… yet.

Slack calls the chat-based applications on its platform “bots,” and for good reason. We always remember that we are speaking to a piece of software, and thus we can forgive it when it misinterprets our language or performs strangely. The bots can have strong personalities — the best ones do — but they don’t try and convince us that they are as human as we are. They know their functions and perform them well.

On the other hand, Facebook’s M attempts to combine human and machine intelligence into one personal assistant. When you interact with M, you’re never quite sure you’re speaking with a human or a bot. At this point, it’s also impossible to stop thinking about the distinction. M might solve the physical friction of actually performing your tasks, but this “Schrödinger’s Bot” approach introduces significant emotional and mental friction for the user. We’re naturally not used to the idea that something can be simultaneously human and inhuman. Covering up the mistakes of artificial intelligence with human intelligence only confuses the issue for the user.

Enhancement: Giving Our Humans Humanity

There is another way to strengthen the link between software and humanity. Instead of giving our software human-like traits, we can give the user superpowers that enhance their humanity, like increased empathy, perception, and creativity. Many messaging tools attempt this, but Snapchat more than any other social product gets this right.

By allowing our shared moments to disappear, Snapchat gives meaning and immediacy to our messages and forces the user to focus their attention on the present. User “stories” allow us to embody friends and strangers, taking on their viewpoints and forming empathic bonds. Live stories create shared experiences that are more than just the sum of our perspectives.

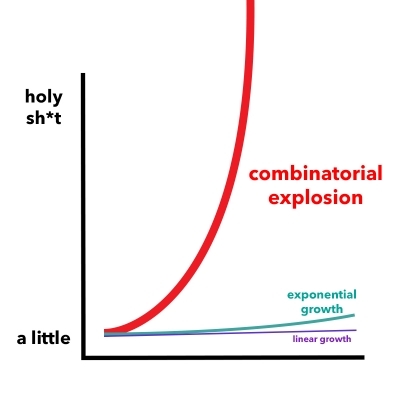

The landing screen for Snapchat is the camera. Anyone with the ability to press a single button can create content, and the product directly encourages this. The limited set of tools (pencils, lenses, text) on Snapchat allow us to be creative without overwhelming us. The strategy reminds me of one of my favorite Brian Eno quotes:

A studio is an absolute labyrinth of possibilities — this is why records take so long to make because there are millions of permutations of things you can do.

The most useful thing you can do is to get rid of some of those options before you start.

Snapchat allows us all to enter the studio, play with our identities and our appearances, and send them without fear of judgment to our network of close friends. This gives Snapchat a strong feeling of “realness” and authenticity. Which reminds me of another Brian Eno quote:

When people censor themselves they’re just as likely to get rid of the good bits as the bad bits.

Snapchat gets rid of unnecessary options and eliminates our need for censorship. As a result, it creates a deeply creative experience around making and sharing content. And most of the time, the content is human faces and bodies. Humans are naturally hard-wired to love looking at humans. Remember how Facebook started?

Speaking of Facebook, they provide a strong counterexample to Snapchat’s humanity. Algorithmically generated “Year in Review” stories approximate a human interaction — making a photo album for your friend — but very clearly fail. Instead of orienting the product around relationships and shared fleeting moments, the focus is on an algorithmic News Feed and profiles that never disappear. Instead of enhancing our empathy, Facebook creates echo chambers and amplifies our strongly held opinions. Facebook does not seem to understand the difference between a recommendation from a friend and an algorithmically-generated recommendation in our Feed.

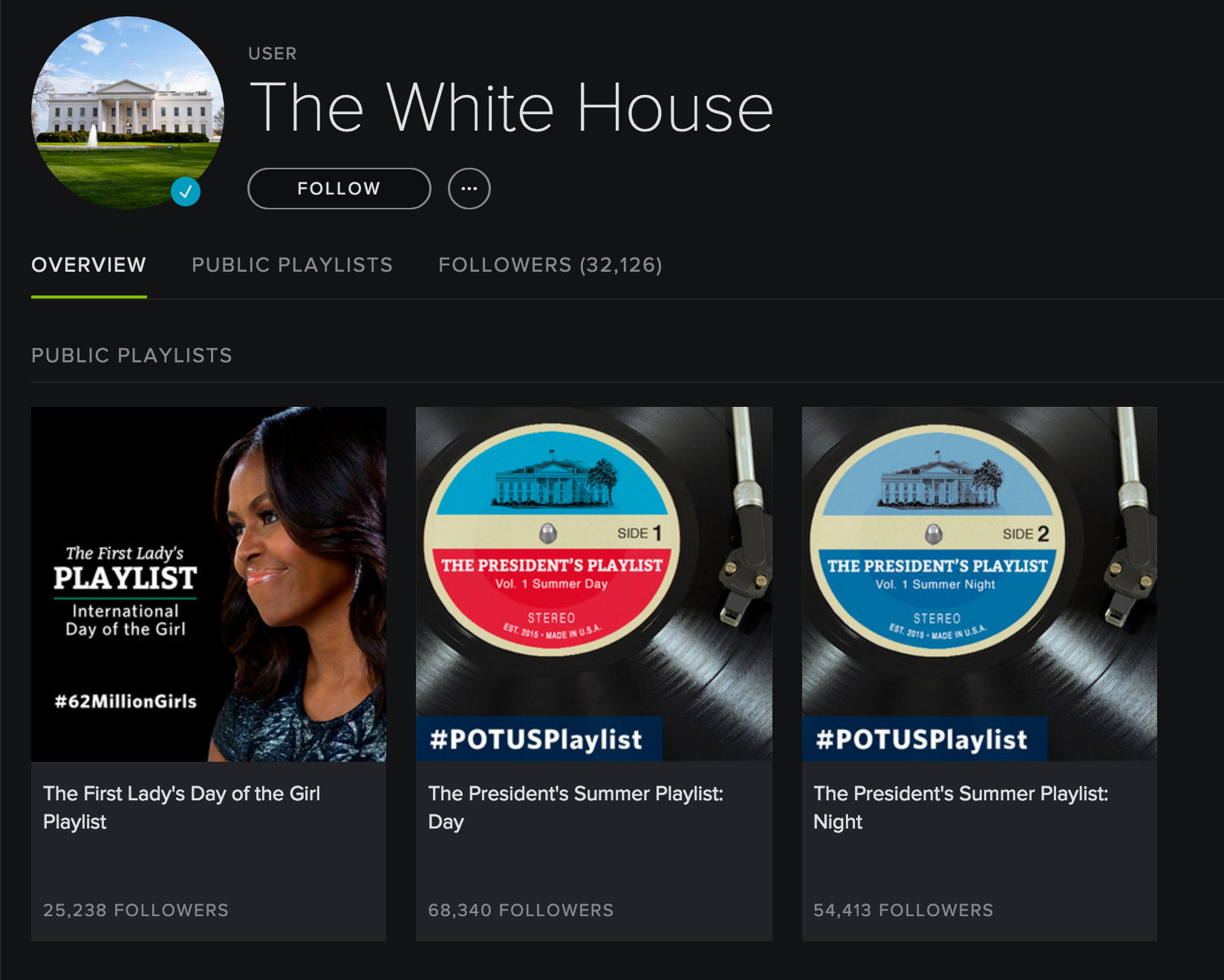

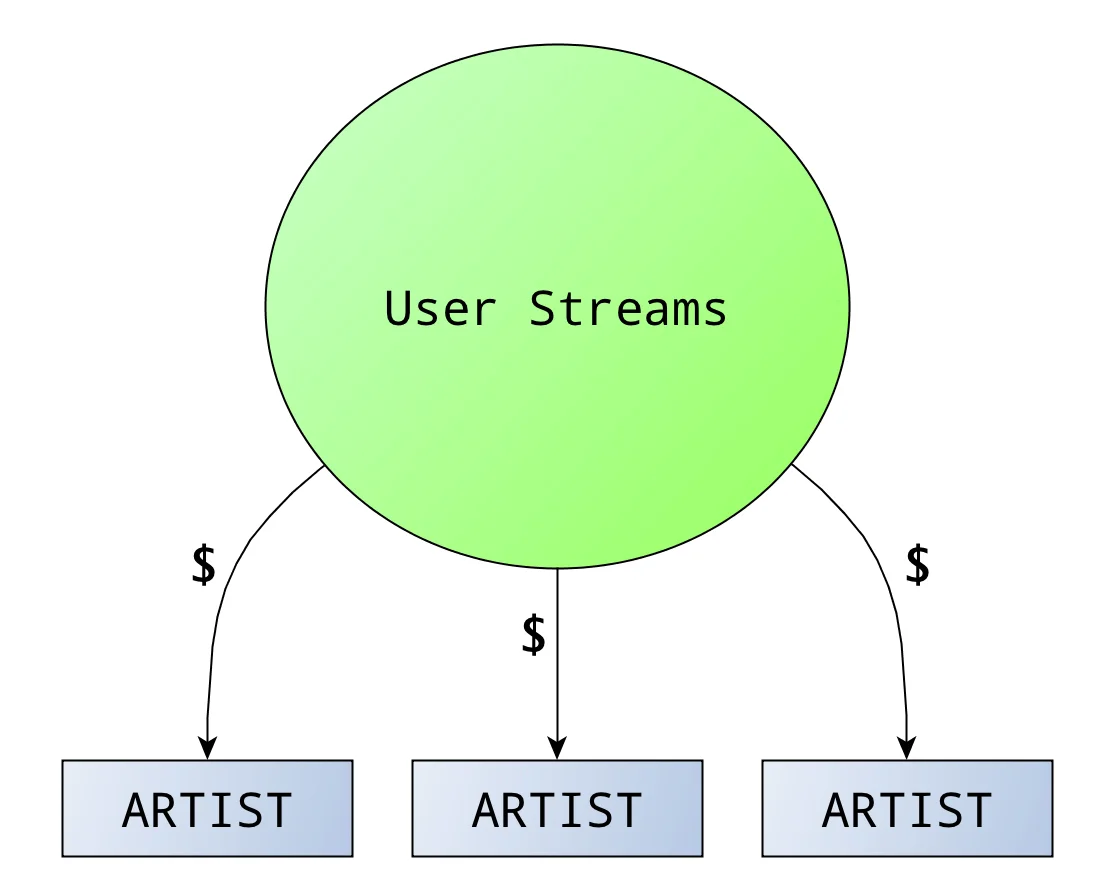

This is not to say algorithmic approximation of human creativity is impossible or unwanted. Some software succeeds in delivering a positive user experience, like Spotify with Discover Weekly. And Snapchat is not the only company who succeeds: YouTube, Periscope and others have all found some success in bringing humanity to their product.

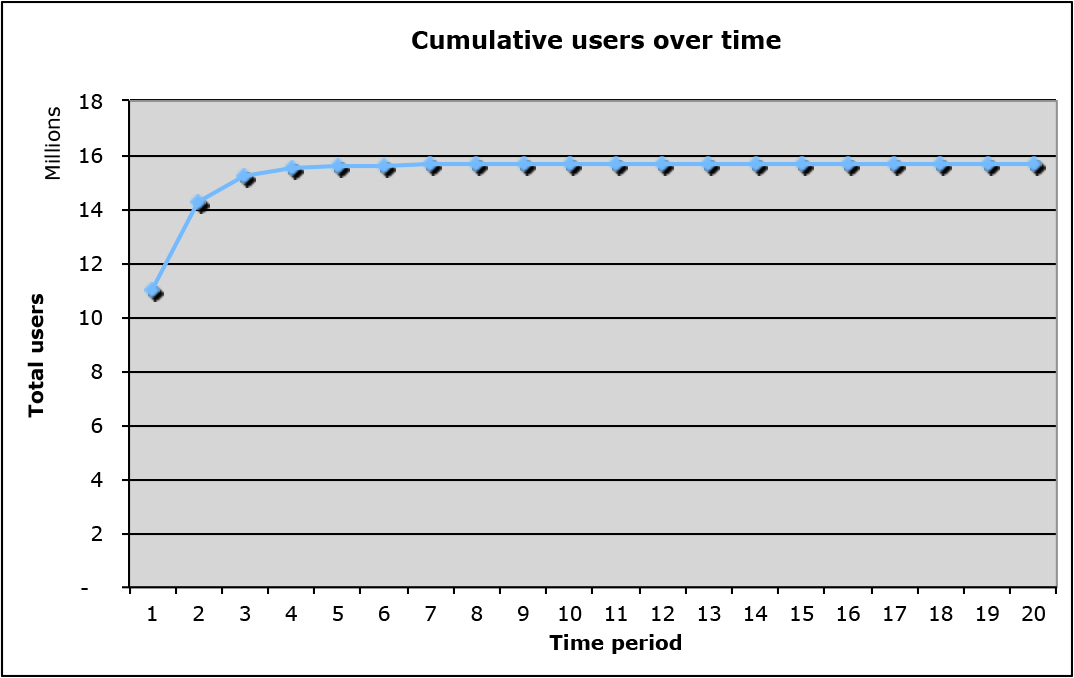

But if you ask me what the best human-oriented social software products in the marketplace are, my answer is unequivocally Snapchat and Slack. Both provide human experiences through endowment and enhancement. Both have friendly, grinning mascots. Both find ways to make collective intelligences and experiences that exceed the sum of the individuals, while still celebrating the uniqueness of our formed identities. And both have undergone tremendous recent growth.

And they’re not just riding a trend. They can potentially define it. When I ask my friends who the “human-first” tech company is, no one has an answer. This is a blank space in meaning that is waiting to be filled — and these are the two companies who can do it best.