What brings down a network?

I’m not really thinking about this in the black-hat hacker sense of “bringing down” networks. I’m more talking about social networks - when and how do they end? What makes them vulnerable?

If you look at Myspace, for example, the end came as the result of a strong challenger (Facebook) and a weak product that succumbed to user exodus after a difficult acquisition by NewsCorp and a series of spam infestations and high-profile investigations.

But there’s one quote in particular from Bloomberg’s report that stands out to me from Myspace’s collapse in particular. "Influential peers pull others in on the climb up—and signal to flee when it’s time to get out.“ It’s rarely a coordinated, consensus-driven decision to abandon ship. The movement is driven by a small number of users who may not even directly call peers to action.

So why are these social networks often susceptible to rapid destruction initiated by a few well-connected users? And which modern ones have done well to protect themselves from collapse?

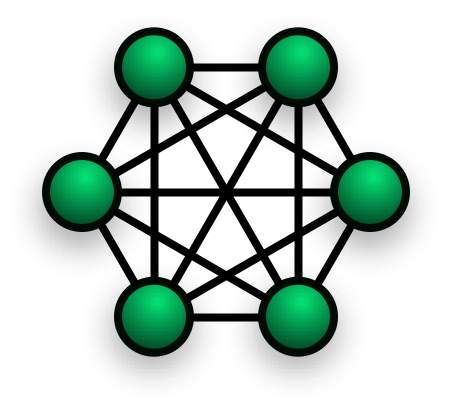

Let’s briefly look at the topology of common networks. Below I excerpt an image from Paul Baran’s paper "On Distributed Networks” from 1964:

A centralized network is one where an individual influencer connects to a number of unconnected nodes - much like a single blogger with thousands of independent followers.

A decentralized network is one where there are multiple smaller influencers that act as hubs connecting individuals and other hubs - this is a good portrayal of Twitter communities organized around a particular subtopic. It is also a good representation of airline route maps.

A distributed network is one where each node in the network has a similar number of connections, forming a sort of mesh as seen in © above. In contrast, decentralized networks conform to a power law distribution where most nodes have only one or two connections, while a small number could have dozens or hundreds.

One of the results of monetization of social networks has been the proliferation of decentralized networks organized around powerful brands and influencers. At this point, the vulnerability of the network is clear - if the hubs are removed, the network collapses. It’s similar to why airport delays in Montana don’t cause havoc, while airport delays at O'Hare in Chicago can bring the entire sky to a standstill.

It’s clearly no surprise, then, that Facebook and Twitter and other platforms bend over backwards to create positive experiences for their top influencers (and revenue generators) while ignoring the best interests of their broader user base.

In Facebook’s early days, however, users’ networks more closely resembled a distributed network. With the platform closed to non-Harvard students, each student on the platform was connected to a high percentage of the full population of other students, forming something like a mesh topology. As other students at other schools joined, those schools’ Facebook networks took similar form. Facebook’s exponential growth was enabled by connecting these strong individual networks.

Lacking distinct hubs, distributed networks are far more stable - the loss of one node does not compromise the strength of the network. Just look at the visualizations from the Baran paper above - which net would you feel safest jumping into?

Like Facebook, many other successful social networks have grown from a stable base of small, unassociated distributed networks. One current example: Snapchat, where users generally have a very small number of strong connections (“Best Friends”) that receive the bulk of their direct communications.

By introducing Our Stories and Discover, Snapchat is allowing users to explore outside of their strong friendship networks and connect across other dimensions such as location or interest. They’ve also done a great job of attracting brands to a still mostly unproven content distribution platform. A brand leaving Snapchat will just leave a void that can quickly be filled by other brands looking to reach young, engaged users.

Snapchat’s strength is in its network topology - people using its core functionality of sharing snaps take the form of a distributed network. Users are engaged primarily not by the presence of brands and artists, but by their close friends. And because most users only need to maintain their ties with a very small number of friends or followers - not the hundreds they might have on Facebook or Twitter - it’s easier for them to keep up a high level of engagement.

Therefore, Snapchat’s weakness might not be its influencer hubs. Rather, it comes from alienating its active users in moving towards a more brand-conscious business model. See: the recent user pushback as Snapchat added Discover but temporarily removed the Best Friends feature. Users were not nearly as upset about the presence of brands as they were about losing that functionality.

I am curious to see how Snapchat and others choose to prioritize features as they seek to attain profitability (or revenue period). But if they fail and fall hard, it will likely be because they burned the net beneath them.