I realized something crucial recently - social media does nothing for me.

That doesn’t mean I don’t use it - if anything, I’m obsessed. I belong to countless groups on dozens of platforms, public and private. I’m plugged in 24-7-365 (and sometimes 366). But most forms of social media are designed for the short attention span, for quick inspiration, for unintentional use - that is, use without intent. When I say social media does nothing for me, I mean exactly that - it actively does not do anything for me.

Modern social media places a significant emphasis on discovery. The bored user, not knowing exactly what they want, is presented with a feed, or a timeline, or recommendations that guide their path through the product. And they’re always being prompted. Add your friends! Upload your pictures! Volunteer your data! Only then can the product give you what you really want to see - at least according to the product.

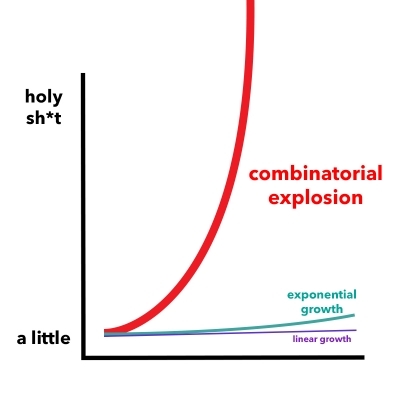

If the user only has a vague understanding of their goals, or only a few minutes to kill, this serves just fine. Sometimes a short video or status update is satisfactory. But most social networks simply serve our neomania - our obsession with the newest or latest information or media. There’s no great depth, only infinite breadth.

But what if I know exactly what I want? Exactly what I’m trying to accomplish? Here social products often fall short.

Social Networks are TV Channels, Not Tools

Let’s use myself as an example. I’m not running a client-based business. I’m not selling a product. I don’t want to primarily use social media as a marketing channel for myself or my interests. I don’t want to primarily use it as a soapbox or a platform. But most of the time, that’s the only utility I can see. And even if I wanted that, the products themselves don’t really tell me how to use them to achieve those goals. They function mainly as channels. Think of YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, or Instagram. The products themselves don’t really tell you how to build a following or how to create great content. And they don’t really care if you do - their primary purpose is to capture your attention for the longest possible time, and repackage that attention for advertisers.

So while it’s great at discovery, social media generally sucks at a couple things particularly - personal support and professional support. And as such, it doesn’t do anything for me - at least, it doesn’t fulfill my biggest needs.

What are my biggest needs really? Even if I were actively selling a product I wouldn’t call that desire to sell a “need" (though it could be a goal). Some of my core needs are personal, and some are professional, but they come down to the same underlying deeper needs - emotional support, a feeling of community, and providing for others.

If we want to establish and maintain communities based around providing and receiving emotional or professional support - communities that enable their members to grow and achieve - we see the power of intention is crucial.

You join a strong community based on intention. You communicate with other community members based on intention. You want to accomplish something, either alone or together. You want to develop an idea or change a mind, even your own. Intending to be someone’s “friend” on Facebook or “connection” on LinkedIn is not really enough - you just know you want to be associated with that person. But how many of your Facebook friends are true friends? How many of your followers would really follow you?

Community and communication are both derived from the same Latin origin - “communis”, or "common". Community is sustained and created through purposeful communication around common interests or goals. How much do you have in common with your high school friends that show up in your news feed? In contrast, how much do you have in common with your work friends or social clubs? Work and social life are communities. Facebook is a bunch of loosely-held acquaintances - on a good day.

So why is it that for so long workplace and social communication tools - intention-based social media - have lagged in performance and character? Why don’t we love those tools the way we seem to love discovery-based social media?

Well, the act of discovery itself drives a lot of our positive feelings towards social media. The idea that our next big idea, our newest friend, our favorite piece of content could be a single click or swipe away is extremely appealing. But really we (and psychologists) know that lasting meaning is developed over time - investing in a skill or community or friendship, reading a powerful book, taking a course, having a career.

Chat and Forums: Networks of Intent

The two most common forms of online interaction for intent-driven communities have been chat and forums. These tools have developed so little in the last twenty years in part because they are so successful. Chat is real-time and personal. Forums create a storehouse of community knowledge. Both can provide emotional support, build community, and allow users to help others.

If you want to really get something done, or really understand something, chances are you belong to a private chat group of experts (maybe on WhatsApp, or IRC if you’re a nerd like me) or an expert forum (perhaps reddit or Stack Exchange). You probably don’t sit on your news feed waiting for the right answers to roll around - and if you do, MY GOODNESS PLEASE STOP DOING THAT.

Those basic forum and chat tools haven’t really changed in decades, yet they retain huge communities and function fairly effectively. I’ve written about why before. But with the rise of new tools, could we finally be entering a golden age of social communication, collaboration and efficacy?

Take Slack’s insane growth rate over the past two years - the team building Slack as a professional productivity tool understands the importance of intention in social communication. The positive psychology of feeling useful to yourself and others comes from intentional, collaborative communication, and Slack’s integrations, automations, and design makes it powerfully productive. Slack took the extra step of adding personal touches like Slackbot for onboarding and GIPHY integration, mirroring the camaraderie and personality of friendships. As a result, Slack provides emotional support, builds community, and allows users to provide directly for others - and that’s the primary function of the product, not a side effect.

This productivity stands in stark contrast to the passive engagement of Facebook or Instagram. Overuse of social media - our leisure time - has been linked to depression, just like overwatching television. Meanwhile, people regularly report feeling most engaged and happy when fully active in the workplace. The real truth is that we need to work, and we need to feel good about our work, and we want to feel good while we work.

I’m done with the old social media. New social communication tools like Slack mix the positive features of social media (direct communication, beautiful design) with the most positive features of workplaces (productivity, integrations, and access to resources). As our social and working lives continue to interweave, there will be an increasing demand for social networks and tools that understand our need to be both personally and professionally fulfilled. That’s why non-professional Slack communities have begun to proliferate even though Slack is currently focused on enterprise.

We want tools that we control, not tools designed to control us. And we want - we need - to be as productive in our social communities as we are in our workplaces.

The future of communication is already here. Our new communities of intention are already being formed. Join us :)